| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

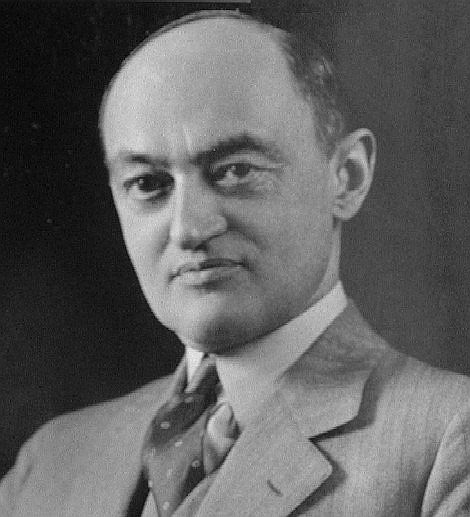

Joseph A. Schumpeter, 1883-1950.

A product of the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Joseph A. Schumpeter exemplified that heritage. Although a student of Böhm-Bawerk and Wieser, Schumpeter was never really a footsoldier of the Austrian School, but cut his own swathe through economics.

Joseph Alois Schumpeter was born in Triesch (Austrian Moravia), the only son of a cloth manufacturer. The Schumpeters were a long-established German Catholic family in a largely Czech town. After his father's early death in 1887, his mother moved to Graz, where Schumpeter received his elementary education. In 1893, his mother re-married a military officer Sigismund von Keler and the family moved to Vienna. His stepfather used his connections to secure Schumpeter's entrance into the prestigious Theresianum school as a day student.

Right after finishing high school, Schumpeter enrolled at the law faculty of the University of Vienna in 1901. Initially interested in history, Schumpeter was lured into economics by his teachers Eugen Philippovich, Friedrich von Wieser and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk Schumpeter obtained his doctorate in law in February 1906, at the relatively young age of 23, and had no clear idea what to do next. Schumpeter spent a summer studying economics in Berlin, then decided to go abroad. Schumpeter spent a year in England, loosely affiliated with the LSE, ostensibly undertaking research for a project on English common law. But in fact, Schumpeter spent much of his time as a man about town enjoying the delights of London. In 1907, Schumpeter married Gladys Ricarde Sever, the daughter of an Anglican dignitary, and soon after took a job with an Italian law firm in Cairo, Egypt. It was a well-paid position and Schumpeter relished the high life of the expatriate elite. He finish his first major work on economic methodology (1908) while in Cairo.

After two years in Egypt, encouraged by the reception of his book, Schumpeter decided to return to Vienna and rejoin academia. Schumpeter submitted his habilitation thesis at Vienna and quickly obtained a job in March 1909 as assistant professor at the University of Czernowitz (east Galicia, now Ukraine) . It was while he was teaching at Czernowitz that Schumpeter wrote his Theory of Economic Development (1911), where he first outlined his famous theory of entrepreneurship. He argued those daring spirits, entrepreneurs, created technical and financial innovations in the face of competition and falling profits - and that it was these spurts of activity which generated (irregular) economic growth.

Bored of provincial Czernowitz, Schumpeter moved on to become full professor of economics at the University of Graz in 1911. Still quite young, the position was secured with critical assistance from Böhm-Bawerk. Graz was then dominated by German Historicists, and Böhm-Bawerk deployed Schumpeter in an effort to capture Graz for the Austrian school. Despite being saddled with a heavy teaching load (all economics courses were foisted on him), Schumpeter found time to write a stream of books and articles during this stage. Nonetheless, Schumpeter found the environment at Graz to be hostile. He jumped at the opportunity to spend a year (1913-14) at Columbia in the United States. When World War I broke out in 1914, Schumpeter's wife refused to return to Austria, and went back to England on her own (they were eventually divorced by 1920). Schumpeter's wartime years were spent rather unproductively in Graz. Schumpeter opposed the war, partly out of Anglophilia, but also partly because of patriotism - Schumpeter feared the war boded ill for the Hapsburg empire, and was merely serving to increase Germany's dominance over Austro-Hungary.

After the war ended, in late 1918, Joseph Schumpeter surprisingly joined the German Socialization Committee in Berlin for Weimar Germany. The invitation had been extended by old Austro-Marxist friends, Rudolf Hilferding and Emil Lederer, from his student days in Vienna, and Schumpeter accepted (as Schumpeter later quipped, "if someone wants to commit suicide, it is a good thing if a doctor is present"). After a few months of discussion, Schumpeter signed the majority report (written by the Marxists) rather than the minority report (of the liberals), agreeing that some kind of nationalization was necessary to make the German economy more efficient.

Schumpeter left Berlin in March 1919 to take up the more alluring offer to serve as Minister of Finance in the new rump state of Austria. The government consisted of a fractious coalition of all parties, only notionally under social-democrat chancellor Karl Renner. Schumpeter was invited not for political reasons, but as a technician to solve the country's economic mess. Unfortunately, the situation in Austria was impossible to manage, and Schumpeter presided over a period of raging hyperinflation, and was dismissed later that year.

After a brief return to teaching at Graz, Schumpeter decided to resign his professorship in 1921. He migrated to the private sector and became the president of a small Viennese banking house. Ill-luck dogged him: his bank collapsed in 1924. He returned once again back into academia - taking up a teaching position at the University of Bonn (Germany) in 1925.

In 1932, Schumpeter failed in his bid to get the retiring Sombart's chair at Berlin University (it went to Lederer instead). Sensing his political leanings were not welcome in Weimar Germany, Schumpeter left to take up a position at Harvard, succeeding the Marshallian F.W. Taussig. He was joined by Alvin Hansen, Wassily Leontief, Richard Goodwin, Paul Sweezy, John Kenneth Galbraith and fellow Austrian, Gottfried Haberler. Schumpeter ruled Harvard during the period of the "depression generation" of the 1930s and 1940s - when Samuelson, Tobin, Tsuru, Heilbroner, Bergson, Metzler, etc. were his students.

Although excelling as a teacher above everything, Joseph Schumpeter nonetheless wrote three more major books while at Harvard: his didactic Business Cycles (1939), his popular Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) - in which he famously predicted the downfall of capitalism in the hands of intellectuals - and his encyclopedic, History of Economic Analysis (1954, incomplete and published posthumously). In the first two, Schumpeter expanded upon his theory of entrepreneurship and theory of growth into a wider theory of the development of capitalism, integrating it into a business cycle theory and a theory socio-economic evolution.

Schumpeter's legacy is difficult to assess. Although an enthusiast of Walras and the Lausanne School, Schumpeter contributed little to it beyond praise. Although his early methodological works had contributed to the Methodenstreit against the German Historicists, the other Austrians had long written him off as one of the faithful. And his old Marxian comrades of Berlin and Vienna certainly did not regard this man with conservative instincts as a fellow traveler.

Like Frank Knight, Schumpeter remains unclassifiable in our schema. Consequently, we give him the honor of founding "evolutionary" economics, given his concern with economic change brought about by the interaction between individuals and the economy as a whole, a concern with socio-economic history and institutions, but not enough to overshadow his search for an inherently theoretical explanation for the development of capitalism.

|

Major Works of Joseph A. Schumpeter

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Joseph Schumpeter

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca